Introduction

Cameraless Photography refers to the practice of manipulating light sensitive photographic paper with only chemicals and without using a camera. The D.P. Henry Archive is greatly indebted to Barret Oliver, (Historian of Photographic Technology and author of A History of the Woodbury type, 2007, Carl Mautz Publishing/ Bardwell press), for drawing attention to Henry’s links with Cameraless Photography for the production of Photograms, or what Henry referred to as his ‘Photochemical Technique’ for producing ‘photochemical drawings’.

Background to Cameraless Photography

The very first experiments with Photography in the 19th. century were in fact cameraless and may be further linked to the Bauhaus and to Man Ray and others in the 1930s. You can research early photography on wikipedia.

From the 1920s to 1950s, photographer Heinz Hajek-Halke used the cameraless photogram for creating photographic abstractions.

In the 1950s, Norman Tudgay, a student at Guildord (later Principal at Medway Art College) experimented with cameraless photograms which he called ‘soft emulsion drawing’ (source: Dr. Jack Tait)

Dr. Jack Tait, a free-lance photographer and former Lecturer in Photography, shares his experiences of Cameraless Photography of the 1960s and 1970s: “At Derby we produced some of this type of work up to 6 feet large for exhibitions and in the 70's I used photograms in my mural design business. I also did similar work for my Focal Press book in the 70's.” (email to Elaine O’Hanrahan, March 26, 2011).

Related literature and links:

Barnes, Martin. Shadow catchers: cameraless photography. Merrell / V&A, 2010.

The 1940s: his inspiration

After serving in WW2 and while studying as an undergraduate at Leeds University (1946-49), Henry and his Belgian-born wife shared his parents’ home in Bramley, Leeds. Following the war, paper was in short supply and knowing his son’s passion for drawing, Henry’s father, Joseph Henry, who worked for Kodak, brought home quantities of waste, photographic, light sensitive paper from fire-damaged warehouses, for his ever inventive son to experiment with. Henry’s ‘making the best’ of this convenient paper source unfortunately led to the family bath being left with semi-permanent purple streaks round its white enamel circumference!

The abstract effects Henry obtained using this photographic paper, he then further embellished by hand to create surreal landscapes inhabited by distorted human figures.

Henry, with his keen interest in Victorian inventions, must have based his experiments on what he had read concerning early photography.

The 1950s

After he moved from Leeds to teach Philosophy at Manchester University in 1949, he continued to develop this cameraless photography technique throughout the 1950s. It was artwork based upon these cameraless photograms which helped Henry beat over 1,000 entries in the London Opportunity competition held by Salford Art Gallery in 1961.

The 1960s

In the 60s, Henry turned his attention to developing his series of three mechanical drawing machines, which have retrospectively earned him the title ‘British Computer Art Pioneer’.

The 1970s

Henry’s return in the 1970s to experimenting with chemicals applied to light sensitive paper, may have been the result of a number of factors, including:

The return in 1972 of his second Drawing Machine in complete disrepair, following the American leg of the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition;

The demise in 1973 of his third and largest Drawing Machine when its axle broke.

Henry’s methods for producing Photograms (1973-82)

In 2000, on learning his grandson Liam O’Hanrahan was doing Art GCSE, my father gave him his photochemical equipment and explained his methods to him.

Here is Liam’s account of how Henry undertook his Photochemical Technique to create Photograms:

“He took photographic paper- the sort that is still used in dark rooms to print pictures from negatives. However instead of exposing this paper to a negative via an enlarger, he placed the photographic paper in daylight with object(s) placed upon it. This would 'over-expose' those parts that had no objects obstructing the light, and would therefore become very dark- leaving a ghostly white 'shadow' of the object. He would then 'fix' this image with photo-chemicals, (in the same way as a photographer fixes an image he has projected onto a piece of photographic paper). However for added effect he would dribble or splash these with photo-chemicals so that only parts of the images would 'fix' and others would fade when again exposed to light, (as light turns photographic paper dark- as described before)”

Henry also added purple Potassium Permanganate crystals to the developer fluid. Its oxidising effects make it one of the principle chemicals used in the film and television industries to “age” props and set dressings so they look “ancient”, as for example on cloth, rope and timber used in films like Troy and Indiana Jones.

Once the paper and its image had been pegged out on the washing line and dried, Henry would press the sheet of paper flat in an adapted Victorian, screw hand printing press his father had given him.

The visual effects

Over a period of ten years, in typical Henry fashion, he explored the exciting possibilities of cameraless photograms to their full.

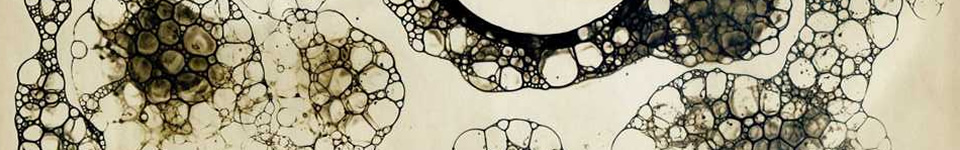

Some images are entirely abstract, without any recognisable forms, resembling a rich soup of organic ‘goo’ accompanied by iridescent effects; others contain shadowy human forms or intriguing objects, shapes and snatches of text. Others again incorporate ‘bubbles’ to create recognisable or evocative shapes some of which are then given latin-based names. A very few were hand embellished, as in his photograms of the 1950s, but for the most part these photograms of the 1970s and early 80s were left untouched by the artist’s hand. Henry’s skills and imaginative intuition as an artist heavily underpinned the selection and arrangement of items to create his original visual effects as did his obvious ability to manipulate the chemicals involved in the capturing process.